So when do we start giving kids an allowance? By first grade at the latest, though there is no harm in starting an allowance sooner. If a child can count and is asking questions about where money comes from and what things cost, then it’s time to begin. Kids who have gotten wise to the power of pestering parents to buy things are ready for an allowance as well. Even if children seem oblivious to money, there is subtle power in having them watch their small piles of allowance money grow bigger over time.

The next task is to figure out how much money a child should receive each week of their allowance. With children under 10, 50 cents to $1 a week per year of age is a good place to start, with a raise each year on their birthdays. We want them to watch the money grow and strive for a goal, so they should have just enough to buy some of what they want but not so much that they don’t have to make plenty of tough choices. Starting an allowance low allows for more frequent or bigger raises if the initial amount doesn’t seem right (and avoids a reduction, which can feel like punishment). Older kids will probably need more money, depending on whether they’re paying for meals or gas or clothing, all of which I’ll talk about in more detail later.

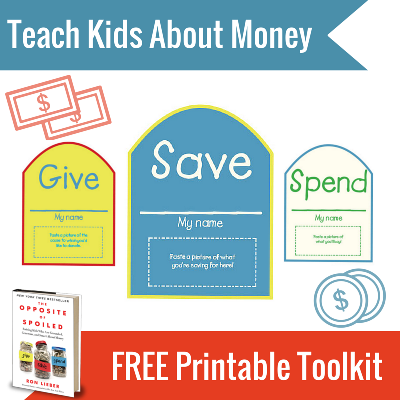

Dividing Allowance into Give, Save, Spend Jars

Once you have an amount, you’ll need a system for tracking and storing the money. In my family, we divide the allowance into three clear plastic containers: one each for spending, giving, and saving. This is, in effect, a first budget. Splitting the money introduces them to the idea that some money is for spending soon, some we give to people who may need it more than we do, and some is to keep for when we need or want something later.

Allowance: The Spend Jar

The Spend container holds money for occasional impulse purchases. If our daughter gets the urge for something small when we’re out and about, we front her the money until we can get home and take it out of the Spend container. We don’t have many rules for this money and consider it a kind of mad science experiment. It’s fascinating to see what moves kids to want to buy something once the money is actually their own. They often want random junk, but this is part of the process of letting them practice. After all, how can we teach them to control their impulses until we observe them under real-world conditions with actual green cash?

Kids who are new at handling money will frequently engage in all sorts of ingenious antics with whatever money you give them access to. Take a boy I know whose mother asked me to keep his name private lest he be embarrassed when he’s older.He had received two $20 bills for his birthday and he insisted on carrying them around in a crumpled lump in his pocket every day despite his parents’ protestations. They decided it would be a teaching moment if he lost the money, but he didn’t (though it did go through the wash a few times). He was waiting for the right moment to use the cash, and it arrived one day at lunch when he decided to buy his way to the front of a long cafeteria line with one of his bills. Rather than wait, he handed a $20 bill over to a child at the front and cut in. Once he’d eaten, he used the other bill on the playground to buy a ball from a friend who had been reluctant to share it. A teacher eventually got wise to the $20 bills floating around and made the two kids give back the boy’s money. Which is really too bad, as it would have been interesting to know whether he felt days later that this was money well spent and how the parents of the newly flush children felt about the emerging underground economy at their school.

Allowance: The Give Jar

The second is the Give container. One way to introduce the idea with younger children is to talk about sharing. In the same way we share our toys with our friends, we also share some of our money with people who need it, except with money we don’t expect to get it back. Talk about times they may have seen you give, to a person on the street or a collection plate at church. Ask them about the things they love to do, whether it’s going to the park or the zoo or the local children’s museum. Chances are, there’s a way to give money to help those institutions, and most of them will have fund-raising staff who will be particularly excited to accept money directly from a child. This, too, is an avenue for teaching patience. Even the youngest children understand that the more money you put in the Give container, the more you can help. Waiting until the container is full before giving the money away will give them a real sense of accomplishment. Families who do a lot of volunteer work should talk about that, too, since money is not the only way to give.

Allowance: The Save Jar

The last allowance container is the Save jar, and we consider it an imperative, a commandment of sorts. Save! But it’s also a joyful exclamation, the sort of thing you’d shout before beginning a journey to a fun destination. One note: Younger kids can have a fuzzy sense of time, so any savings goal should be relatively short term at first. By keeping the goals modest, there’s a better chance of meeting them. Make them concrete, too; it can help for children to cut out a photograph or draw a picture of whatever it is they’re saving for and tape the visual onto the container itself.

Figuring out how to delay gratification is a key part of handling money well. – Ron Lieber

Keep things easy at first by putting an equal number of dollar bills in each container. Alternatively, divide things up so that you need only singles and no change, say, by distributing $2 each week for both spending and giving and $4 for saving. After a few years, consider allowing the children to decide how to divide the money. At that point, there can be an extra incentive for saving. Financial planner Brent Kessel and his wife pay interest on the money their kids save and that which they set aside for charity. Their interest schedule starts off quite generous—anything under $50 earns 50 percent each month. (Yes, not each year but each month; if only banks worked like that.) All money under $100, however, earns just 25 percent in interest, and the rate continues to fall as the balances rise. Eventually the interest falls to a 1 percent monthly rate on anything above a $2,000 balance. I thought this was a bit odd; why not pay even more as they save more to reward their patience? “I found they over-saved even with this schedule,” Brent explained. “Which is why I dropped the interest amount at higher levels. They would have bankrupted me otherwise!”

Gifford Lehman, a financial planner who lives in Monterey, California, gave his kids a choice. They could pay a 15 percent tax on their allowance, which he would make them physically hand back to him to make it tangible. Or, they could set aside twice as much as the tax (30 percent of the allowance, in that case) and then collect a 100 percent match (turning a 30 percent savings rate into 60 percent). This might seem like a no-brainer, but it isn’t always easy for kids (or adults) to be patient enough to wait around to collect on that 60 percent. The unspoken understanding in the Lehman household was that the matched savings was for goals that were years away. If the matching numbers are big enough, many kids will get in the habit, as Lehman’s kids (now grown) did. And it’s a useful habit, since employers often reward retirement savings in the same way in 401(k) and similar plans by matching some of the workers’ contributions.

Allowance: Make a Commitment

Whatever rules you set for spending, giving, and saving, starting a weekly allowance is a commitment, so it will help to get a few things squared away ahead of time. First, there are the containers themselves. I hate piggy banks, and the problem begins with the metaphor itself. Pigs are dirty, and they eat a lot, so piggish behavior isn’t something to aspire to. And the idea that you’re somehow a hog if you save money isn’t accurate. Meanwhile, ceramic or metal containers are problematic, since we want kids to be able to see what’s inside and watch it grow. Also, it should be easy to put bills in and take them out. Tiny slots or complicated openings that require folding bills into little squares don’t work well. After trying a couple of different solutions in our family, we finally defaulted to the clear plastic bins that Rubbermaid and others sell as containers for cereal or rice, and our daughter decorated them.

Next, the money to put in the containers needs to be available on the chosen day each week. We did two things to make sure we had enough of the right bills on the right days. First, I started hoarding $1 bills, depositing them in a bowl in our apartment every few days. Then we joined the credit union at our office specifically so we can drop in any time and exchange a few $20 bills for a stack of singles. We also set a calendar alert for each Saturday morning so we would remember to distribute the money, though our daughter now remembers herself most of the time.

In some families, children may have savings accounts that family members have seeded, but they come with strict instructions that the kids aren’t to touch the money for a good long while. Kyle Jones and his sister, Stephanie, grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His maternal grandmother worked as a housekeeper and earned $1 a day when she first started out. “If you think about that movie The Help, well, she was the help,” Kyle said. Her husband died young, but she still managed to help Kyle’s mother through college and graduate school.

Though her wages remained low throughout her life, she was careful with her Social Security check, and she had a bit of savings when she died. Kyle was 11 years old, and once the family paid the bills for the burial, there was about $10,000 left. Kyle’s mother, Mary Louise, already had strict instructions about what was supposed to happen to it. “My mother had told me to take whatever was left and save it for Kyle and Stephanie,” she said. “She didn’t care about me.”

So Mary Louise put the money away, and Kyle and Stephanie were only vaguely aware of it. They knew better than to ask for any of it either, even for college, for which they both took out loans. In this family, the money has a specific purpose. “The idea of creating generational wealth is something new in the black community, because there isn’t a lot of old money per se,” said Kyle, now a grown man living in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and working in finance. “I don’t even think of that money as real. I get the tax form each year, but it’s not for my everyday life. I need it for my next life. It’s almost as if my mother has shamed me for it. It doesn’t exist!”

Get the Free Printables! Download the Give, Save, Spend Jar Labels and More!

Download the Money Responsibility Toolkit and Give, Save, Spend jar label printables here.

Excerpted with permission from The Opposite of Spoiled: Raising Kids Who Are Grounded, Generous, and Smart About Money by Ron Lieber, copyright Ron Lieber, 2015 (HarperCollins Publishers).

* * *

Your Turn

Do you give your kids an allowance? What are some struggles you’ve had with teaching your kids about stewarding money well? Join the conversation on our blog! We’d love to hear from you!